Photography by Martin Parr; Set Design: Michael O’Connell; Food Stylist: Loic Parisot

Courtesy of OTHERWAY

In a 1523 letter to his stonecutter, Michelangelo wrote: “You will have heard that Medici has been made pope, because of which, it seems to me, everyone is rejoicing and I think that here, as for art, there will be much to be done.” Just a few days earlier Cardinal Giulio de’ Medici had been elected Pope Clement VII, reigniting the Medici family’s influence not only over Florence but over the entire Catholic world. For Michelangelo, this was a signal: art would soon be needed. Commissions would flow. He knew that patrons like the Medici were curators of meaning, crafting their image through the talents of painters, sculptors, and architects.

Centuries later, the core mechanics of this dynamic remain intact, albeit in new forms, finding striking echoes in the behavior of global brands. In fact, from luxury fashion houses to tech platforms and beauty conglomerates, new stakeholders have emerged as cultural patrons. These include Prada, Adobe, L’Oréal, BMW, and Audemars Piguet, with more joining their ranks every year. Like the Medici, they invest in culture not merely to support it, but to shape it. Their aim is—now, as then—relevance, resonance, and soft power. But as modern brand-artist collaborations proliferate, they raise familiar questions: Who really shapes culture? What values are being amplified? And in a media-saturated age, what does meaningful patronage look like?

© Horst P. Horst, Vogue / Condé Nast; © Estate Of George Platt Lynes

Courtesy of Getty Images

Image Rights of Salvador Dalí reserved. Fundacio Gala-Salvador Dalí, Figueres, 2017

Patronage through the ages

Historically, patronage has always been an instrument of influence and prestige. At the time of Michelangelo and during the modern era, commissions—whether from princely courts, the papacy, or powerful merchant families—served to express political power, project theological authority, and build lasting legacies. With the decline of ecclesiastical and aristocratic dominance in the 19th century, industrial barons followed suit, offering what Clement Greenberg famously described as the “umbilical cord of gold,” meaning the financial support provided by the elite that enables artistic innovation—even to movements that claim to stand apart.

Magnates like the Rockefellers began to fill the void, leveraging private wealth to shape public culture and, often, polish their legacies through the creation of libraries, museums, and cultural foundations. In the 20th century, philanthropic figures like Peggy Guggenheim extended the tradition into the avant-garde, using personal wealth to both collect and champion artists on the margins of the mainstream, contributing to the definition of a new era of art across continents.

Today, the “umbilical cord of gold” persists and it increasingly connects artists not only to collectors and institutions, but to corporate entities with marketing strategies and evolving brand identities. Patronage has become less about eternal legacy and more about cultural positioning as an unprecedented number of brands adopt and adapt patronage models as strategic cultural investments that influence public perception and drive the direction of culture itself.

At a time when the rapidly evolving media landscape has made conventional advertising channels more challenging, brands—like the new Medici—commission artists, partner with institutions, fund cultural projects to construct narratives that bolster their identities while projecting cultural authority, thus echoing the very old idea of culture as a timeless currency. Contemporary patronage, once again, is more than supporting art; it is a means of influencing which voices are elevated, what narratives endure, and how societies come to see themselves.

As artists become a conduit through which the brand aligns itself with contemporary values—sustainability, inclusivity, innovation, heritage—they receive resources, visibility, and reputation. In The Curious Economics of Luxury Fashion, Don Thompson likens artists’ paid collaborations with brands to actors taking commercials, leveraging the scale of the luxury goods market, which dwarfs that of the art world, to reach vastly larger audiences. Yet, this dynamic reveals a tension and underlying question at the heart of modern patronage: can brand interests and cultural strategy coexist with creative freedom?

Mondrian, The Miami Herald Part II, October 31, 1965, 19E.

© 1965 McClatchy. All rights reserved

Why do brands invest in culture?

In the early 2000s with a bestseller titled How Brands Become Icons, former marketing professor at the Harvard Business School and then L’Oréal Chair of Marketing at Oxford Douglas Holt introduced the so-called ‘cultural branding theory’, which he later developed into a ‘cultural strategy’ model. This hasn’t necessarily to do with creative production, but rather how brands become powerful more for what they symbolize than for what they sell. However, within this marketing framework that is set to leverage cultural shifts and ideological opportunities on the path to corporate myth-making, the concept of cultural proximity—the alignment with cultural capital and values—has become a critical resource. Luxury brands, in particular, engage in what researchers have called “artification,” aligning themselves with the authority of art to signal sophistication and taste.

The cross-pollination of art and luxury, especially fashion, isn’t something novel. Just think of Elsa Schiaparelli’s collaboration with Salvador Dalí in the 1930s or Yves Saint Laurent’s 1960s cocktail dresses inspired by Piet Mondrian’s signature grids. However, in the era of mass production, these ties have become more and more conscious and strategic. Within this process where art reinforces the symbolic authority of luxury, brands amplify artists’ reach and credibility in a symbiosis that extends well beyond luxury.

Brand cultural patronage takes multiple forms, often shaped by the nature of the brand’s goals and the type of artist involved. Commissioning remains one of the most direct models. For their 2025 summer campaign, upmarket department store Fortnum & Mason invited iconic British photographer Martin Parr, known for his unfiltered and subtly humorous representation of everyday life in UK’s coastal towns, to capture the quintessential British summertime. Parr’s distinctive visual wit provided a fitting narrative for a heritage brand seeking contemporary relevance without losing its roots; a successful collaboration with a shared cultural identity at its heart.

Sometimes patronage exists in the shape of partnerships. A notable example is L’Oréal Group’s three-year alliance with the Louvre, which includes a bespoke museum tour tracing the history of beauty through 108 selected artworks. By weaving its brand into one of the world’s most respected cultural institutions, the beauty giant aligns itself with both artistic prestige and contemporary values like diversity and inclusivity that are extremely important to younger, socially conscious consumers that L’Oréal aims to target. The iconic museum, on the other hand, alongside the (undisclosed) financial support, has gained a new way to attract local audiences, adding fresh value to the visitor experience. This also speaks of the characteristically post-pandemic need, for both brands and museums, to build engaged communities grounded on emotions, interests, and real-life experiences.

Sponsorships, too, are getting increasingly sophisticated, with the 2024 Venice Biennale’s international exhibition Stranieri Ovunque – Foreigners Everywhere drawing sponsorship from Dior—a hint to Christian Dior’s early career as a gallerist—and luxury fashion houses such as Burberry and Tod’s lending support to the British and Italian Biennale pavilions, respectively. In some cases, brands simply invest in spatial or symbolic proximity to cultural capital. Strolling along Milan’s opulent Via Montenapoleone, for example, what might, at a first glance, resemble an art gallery will reveal itself as Tiffany & Co.’s new flagship displaying striking works by blue-chip artists such as Pablo Picasso, Urs Fischer, and Michelangelo Pistoletto. These curated environments serve as more than aesthetic backgrounds; they cement the brand’s place within a lineage of taste, value, and cultural legitimacy.

Courtesy of TPS Productions/Focus Features ©2025 All Rights Reserved

Léa Seydoux stars in ads for Louis Vuitton’s collaboration with Jeff Koons

Courtesy of Louis Vuitton

Photography by Martin Parr; Set Design: Michael O’Connell; Food Stylist: Loic Parisot

Courtesy of OTHERWAY

The responsibility of brands in cultural production

With influence comes responsibility. In fact, the flipside of such injection of branded capital is the potential commodification and flattening of complex artistic expression, especially if they are perceived as somehow “difficult”—perhaps seen as too conceptual, radical, or simply not Instagrammable enough. Critics warn of collaborations that veer into tokenism, and superficial trend-chasing, undermining the credibility of both artist and brand.

The ill-fated Jeff Koons x Louis Vuitton Masters collection from 2017 is a cautionary tale. Despite its visual spectacle, the collection featuring printed works by Van Gogh, Da Vinci and others on Louis Vuitton Speedy bags was widely seen as lacking genuine artistic intent, serving more as prestige borrowing than meaningful cultural dialogue and failing to engage audiences effectively. This example shows how, increasingly, successful brand patronage it’s not just about association; it’s about authentic alignment, shared values, dialogue, and that right amount of creative disruption that respects both brand identity and artistic freedom—freedom to experiment, critique, and introduce complexity. Marc Jacobs, former Louis Vuitton creative director, reflected on this complexity when Pop artist Takashi Murakami realized an in-gallery Louis Vuitton boutique for his solo exhibition at MOCA Los Angeles in 2007: “What is the art here? […] It operates on so many levels that it’s hard to categorize. I thought, Well, isn’t that what the state of art is right now? It’s not so easy to define.” In contrast to the Masters collection, the partnership with Murakami—just one example in a string of fortunate collaborations between the French couture brand and the Japanese artist—succeeded because it embraced ambiguity and layered meanings.

This expanded role also requires a long-term vision that goes beyond transactional partnerships and prioritizes sustained engagement over fleeting campaigns. Things can get even more complex when it comes to cross-cultural collaborations. While these hold a strong potential for cultural resonance, telling richer stories that engage audiences through cultural sensibility, they require deep cultural literacy specific to the local context. Here is where cultural strategists, agents, curators, and producers come into play. Not only do they provide crucial and nuanced understanding of the cultural context; they mediate between commercial aims and artistic integrity. What’s more, they can help negotiate equitable collaborations, ensuring fair and transparent agreements. In fact, while it’s fair to argue that brands offer, often alongside generous budgets, the infrastructures to reach wider audiences, artists often hold the most vulnerable side of the deal, which creates the need to negotiate contracts, define fees, best practices, and, overall to make brand collaborations an organic fit into a sustainable artistic career, ultimately balancing a power relationship that might otherwise be asymmetrical.

Let’s take a closer look at selected manifestations of contemporary patronage, each embodying different facets of how corporate actors navigate cultural production today.

Courtesy of Chanel/Roe Ethridge via WWD

Chanel’s Arts & Culture Magazine: building cultural capital in print

In June 2025, Chanel launched Arts & Culture Magazine, a visually driven print publication dedicated to the maison’s links with the artistic world. The release falls within the brand’s rich history of cultural patronage, which dates back to Coco Chanel’s collaborations with avant-garde artists such as Salvador Dalí, Pablo Picasso, and Igor Stravinsky, and culminated in the creation of the Chanel Culture Fund in 2021—a global program supporting cultural innovators, which also spearheads the Arts & Culture Magazine project.

Alongside the (perhaps inevitable) abundant promotional Chanel content, the 250-page tome features thoughtful essays, interviews, and art projects that intersect with contemporary cultural conversations. Although not the first publication of this kind (most notably, the beautifully produced Acne Paper by the Swedish creative collective and fashion label Acne Studios), Chanel’s Arts & Culture Magazine strategically leverages the comeback of independent magazines and bookstores, looking for fresh ways to engage a younger, more discerning audience at a time of shifting attitudes toward luxury. According to Emily Huggard, professor of fashion communication at Parsons School of Design: “This magazine shows how brands want to now link themselves to enduring culture, instead of transient moments. For Chanel, this also allows them another way to tell their historical story, which can get tiring to do.” In the midst of transition for the maison—with a reported drop in sales in 2024 and a new artistic director—the debut into print media further expands the brand’s narrative beyond the runway, strengthening its commitment to global creative innovation.

WeTransfer’s WePresent: a platform for authentic artistic voices

On the topic of non-conventional editorial platforms, WeTransfer’s WePresent exemplifies how brands outside luxury are embracing patronage. What started in 2018 as a place to showcase and promote all the WeTransfer wallpapers the well-known file-sharing company had commissioned to artists from all over the world has developed into a diverse editorial and creative portal that commissions original projects across art, music, photography, film or literature to celebrate the impact of creativity on the world that surrounds us. Working directly with international artists, they aim “to be the most representative creative site on the internet.” They have collaborated with creatives including Marina Abramović, Olafur Eliasson and Bernardine Evaristo among many others. For some time over the years, WePresent also took the form of a print magazine, produced with a unique publishing model—each issue published in three distinct graphic design iterations—to reflect a commitment to multiplicity and experimentation that is rare in branded content. Today, WePresent is a fully digital arts platform and serves as a compelling example of how brands can foster creativity by prioritizing artistic freedom and complexity over formulaic campaigns.

Saint Laurent Productions & Fondazione Prada Film Fund: fashion’s leanings into cinema

A recent trend in building cultural and social capital is fashion’s expansion into cinema—a form of patronage that goes well beyond Hollywood stars wearing branded haute-couture outfits on red carpets. In 2023, Saint Laurent became the first fashion house to include full-fledged film production in its portfolio, bringing, with Saint Laurent Productions, three films at the Cannes Film Festival. Similarly, in 2025 Fondazione Prada announced its entry into the film making industry with the Fondazione Prada Film Fund, a yearly initiative to support independent cinema. The ties between fashion and cinema are getting so intertwined that sometimes they also work in a reversal of roles—the artist commissioning a sellable fashion product. This is for example the case for a stylish pair of Oliver Peoples sunglasses, specifically commissioned by Wes Anderson for his latest film The Phoenician Scheme. In addition to the pair used in the film, the eyewear brand has produced ten extra hand-made frames featuring the film’s logo, available in selected boutiques from the film’s release date.

Photography by Shanna Besson

©2024 The Absolut Company

Absolut’s The Other Half: spotlighting underrepresented artists

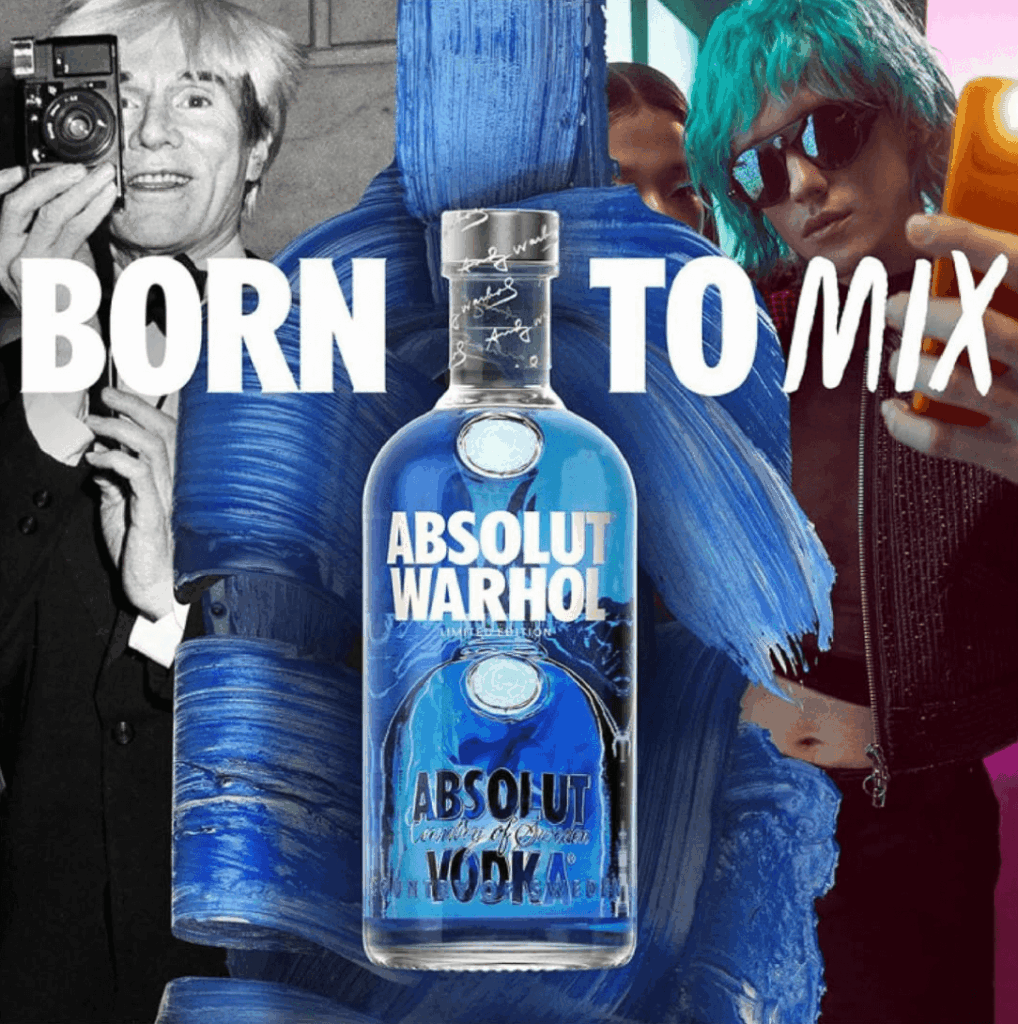

In 1985, Andy Warhol, who notoriously didn’t mind stepping into the commercial world, produced an artwork based on the silhouette of Absolut’s distinctive apothecary-inspired vodka bottle. His output became the brand’s first art advert and marked the beginning of its long-standing history of artistic collaborations icons—over 500 in total, some of which with seminal artists including Keith Haring, Louise Bourgeois, Nam June Paik.

When a second 1985 Absolut painting by Warhol, known as the ‘blue’ one, was unveiled at auction in 2020, the brand took the opportunity to strengthen its commitment to creative production with The Other Half campaign. This initiative aimed to emphasize the values of inclusivity and diversity through the work of underrepresented voices in contemporary art—revealing how brands can align cultural patronage with values-driven social impact.

As part of the campaign, Absolute asked five emerging artists in the UK to design “the other half” of the Absolut ‘blue’ painting and, in partnership with Saatchi Gallery, provided them the opportunity to showcase their work in a high-profile gallery.

As Marketing Manager Alison Perrottet noted: “The Other Half initiative continues to expand on Absolut and Warhol’s common legacy of challenging the norms and embracing inclusivity—and will hopefully solidify Absolut’s place in contemporary culture!”

Towards the future of brand patronage

These case studies show how, in the shifting landscape of postmodern consumption, where not only objects but contents and ideas are consumed too, corporate entities influence artistic production and cultural narratives on an unprecedented scale. Strategic cultural investments, if executed thoughtfully, can empower creators and contribute to cultural enrichment. After all, the appeal of artist-brand collaborations is mutual, making successful patronage not (only) a matter of credibility borrowing but a joint effort to build cultural value that resonates far beyond the marketplace, blurring the lines between disciplines and shaping the cultural discourse in meaningful ways. There are of course other stakeholders involved and other models for cultural funding, which remain essential for a healthy and genuine cultural ecosystem. Still, centuries apart from the Medici, companies are poised to play a key role in redefining what it means to be patrons of culture in the contemporary era. Brand patronage’s development surely is a critical space to watch.

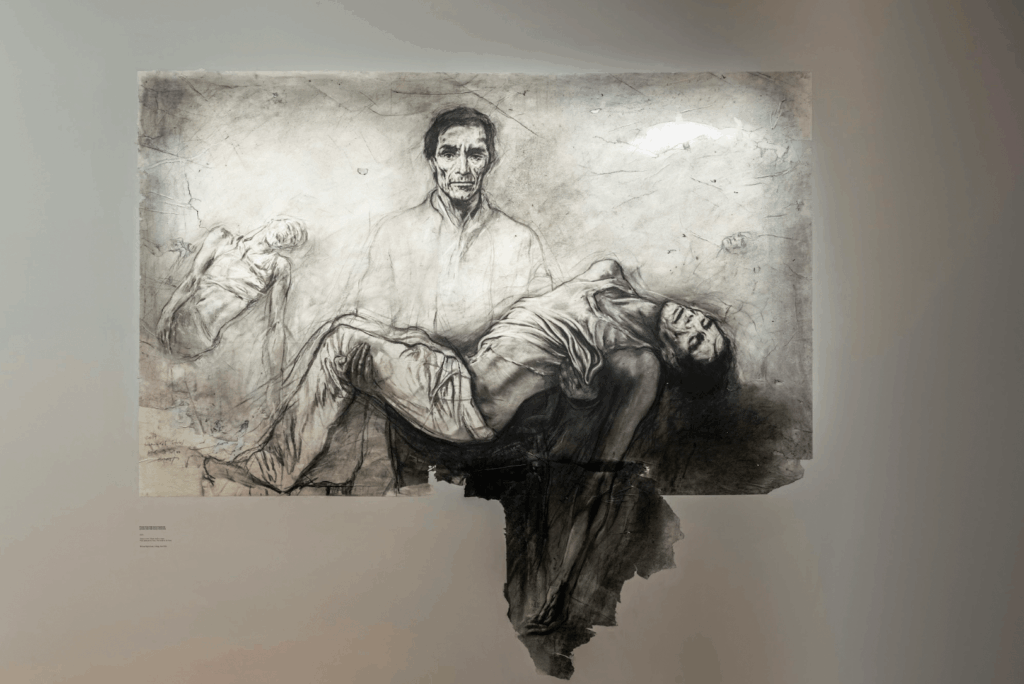

Étude Pour Pier Paolo Pasolini

Courtesy of Ernest Pignon-Ernest and ADAGP, Paris 2024

Photography by Daniele Nalesso, courtesy of Louis Vuitton

Practical guide for navigating Brand-Artist collaborations

Designed for both brands and artists seeking to engage in meaningful collaborations, here is a list of tips that will help ensure you’re starting on the right track.

For Brands:

- Focus on cultural fit over chasing trends. Authentic resonance builds lasting credibility.

- Define clear objectives and audiences to align creative efforts with strategic goals.

- Establish clear KPIs, but don’t force them into creative metrics. Balance brand objectives (e.g. engagement, awareness, brand sentiment) with room for artistic process and unexpected outcomes.

- Respect artistic integrity.

- Ensure legal clarity from the outset.

- Engage cultural mediators to navigate local contexts authentically.

- Invest in long-term relationships that foster trust and ongoing dialogue.

For Artists:

- Research potential partners’ histories and cultural credentials carefully.

- Set firm creative boundaries and ask yourself: does commercial motivation limit my creative liberty?

- Don’t self-censor—be ready to educate the client. If your work carries cultural or conceptual significance, take the time to explain why it matters. Many brands are open to engaging with deeper ideas if they’re framed thoughtfully and communicated clearly.

- Keep your audience in mind without compromising your voice.

- Negotiate fees, intellectual property rights, and licensing terms fairly i.e. don’t undervalue your work.

- Clarify usage terms—and limit them strategically. Consider the duration and geographic scope, exclusivity (could it restrict future opportunities?), and reproduction formats (physical, digital, or derivative works such as merchandise or marketing assets).

- Seek partnerships that offer growth opportunities i.e. think beyond exposure. Could this collaboration lead to gallery invitations, institutional recognition, or long-term art commissions?

Words: Benedetta Ricci